Knowledge-Intensive Processes

As depicted by Di Ciccio and his collaborators, Knowledge-Intensive Processes are characterized as knowledge-driven, collaboration-oriented, unpredictable, emergent, goal-oriented, event-driven, constraint- and rule-driven and non-repeatable. Covering a wide range of processes with different degrees of flexibility and predictability, KIPs can be used to denote modern business processes where interactions between humans and computers are the norm. Typical examples for KIPs are processes used in hospitals and clinics where doctors, nurses and staff are immersed in a collaborative and computer assisted context to execute several procedures that are hard to formalize and prescribe using workflows and rules. There are also processes such as making a scientific publication or composing a song where several characteristics from each participating individual, such as past experience, tacit knowledge, mood and context, influence how the activities are executed, making them hard to predict.

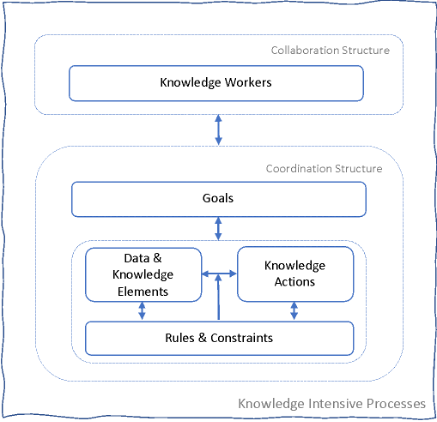

Important to our agenda is how Di Ciccio illustrates the fundamental components of a KIP (Fig. 1). A high-level perspective indicates KIP has the Collaboration and Coordination structures that can interact in both directions. The Collaboration Structure encompasses the Knowledge Workers, who are the “knowledgeable” individuals interacting (are part of) with the process. In a KIP, Knowledge Workers are supposed to be free to execute the process at their discretion, meaning they can skip activities, re-execute activities or even create new activities during execution. They may also use different data that the prescribed.

The Coordination Structure aims at organizing the components that define the process structure and contains Goals, Data & Knowledge Elements, Knowledge Actions and Rules & Constraints sub-components. Goals capture the intents related to executing a KIP, typically using the Knowledge Workers language. To achieve goals, Knowledge Workers execute Knowledge Actions using Data and Knowledge Elements and are subject to Rules and Constraints. Knowledge Actions indicate chunks of work that can be executed and can be seen as BPMN activities. Data and Knowledge Elements specify the data/elements that are used when executing the actions and they resemble BPMN Data Objects. Last but not least is the Rules and Constraints sub-component that tries to limit the KIP’s flexibility by imposing some restrictions on how activities are performed, and data is used.

A simple example of KIP is an Agile Software Development Process (AgileSDP). An AgileSDP may have several goals (KIP- Goal) such as to deliver the software system incrementally or promote end-user commitment. For that, the AgileSDP is broken down into activities (KIP - Knowledge Action) such as Create Vision Document, Create Test Case or Deploy System Increment. To Create a Vision Document (KIP - Data), a Software Engineer (KIP – Knowledge Worker) might interact (KIP - Knowledge Action) with end-users (KIP – Knowledge Worker) and management (KIP – Knowledge Worker). The process may have constraints such as increments must be delivered every 3 weeks or tests must cover 100% of the code (KIP - Rules). When executing such AgileSDP, the Software Engineers (KIP – Knowledge Worker) may decide they will comply to just 70% of test coverage, because a team member is absent.

We can also understand the endeavor of planning a family trip as a KIP. We all know to plan a trip: we need to define the dates, define who is going, buy the tickets, book the hotel, reserve car, buy insurance and reserve attractions. Although the Trip Planning tasks seem straightforward, they might be considered as part of a KIP because: Which order should we execute the tasks? Buy Ticket first or Reserve Hotel first? Skip Insurance for everybody? What happens if Uncle John decide to join the trip? How do we maximize our goals?

There are so many alternatives and nuances related to KIPs that defining a model to govern them all is practically impossible. Investigating better ways to represent, execute, monitor and improve such types of processes is at the center of this research agenda.